The drought will likely continue into the fall and winter.

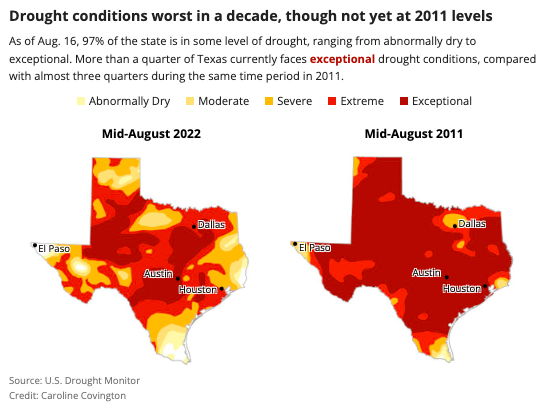

Texans across the state are facing water restrictions as the state experiences its worst drought since 2011.

Almost the entire state of Texas is experiencing a severe level of drought, and only a few corners of the state, such as El Paso, are not “abnormally dry” amid this year’s particularly hot summer.

And while the state is seeing some pockets of rain in late August, the drought likely will extend into winter because of current climate patterns that could lead to hotter and drier weather.

What is the definition of a drought?

A drought is generally defined as an extended period with little to no rainfall that leads to a water shortage, according to the National Drought Mitigation Center.

A drought can begin with a dry spell and quickly develop within a month or two of dry conditions in the summer and with more time during the winter, said John Nielsen-Gammon, the Texas state climatologist and a regents professor at Texas A&M University.

The U.S. Drought Monitor classifies drought conditions into five categories based on how unusual the dry conditions are in an area at a given time of year according to climate data, Nielsen-Gammon said.

In Texas, about 27% of the state is under an “exceptional drought,” the most severe category, and about 62% is under an “extreme drought,” the second-highest classification, according to the monitor’s latest report.

What is causing the Texas 2022 drought?

Texas has been in a drought since September 2021, Nielsen-Gammon said, and that’s due to several factors, including climate patterns in the tropical Pacific Ocean.

When the surface water in the tropical Pacific Ocean near Mexico and South America warms more than usual, it is known as a climate pattern called El Niño, which can help fuel more rain in Texas and the southern U.S.

But when it is cooler than normal, the climate pattern is known as La Niña and tends to shift rainfall and cooler temperatures toward the north of the U.S., leaving the south with drier and hotter conditions.

La Niña primarily affects the U.S. during the winter, but it has now favored drier conditions in the south for two winters, exacerbating Texas’ drought.

The weather this summer, including triple-digit temperatures, also intensified drought conditions. The high temperatures, which have also increased overall because of climate change, make it easier for water to evaporate and harder for soil to retain moisture.

“We’ve been having several months of exceptionally high temperatures and below-normal rainfall, and as long as that’s going on, drought conditions get worse,” Nielsen-Gammon said.

For more information, visit the U.S. Drought Monitor website.

For more information, visit the U.S. Drought Monitor website.

What are the effects of this drought in Texas so far?

The drought conditions have primarily hurt agriculture in Texas so far. For example, Nielsen-Gammon said ranchers have sold off their cattle for meat or to other areas because they can’t afford to keep them under the drought conditions.

“We’ve seen a very large increase in sell-offs of cattle, in some cases entire herds, because of lack of forage, lack of water and [the] prohibitive cost of bringing in provision feed and water from outside,” he said.

While this means ranchers can still bring in some income right now, it also means they’re giving up profitable cattle that they could use to raise more calves in the future. And rebuilding a good herd requires time and effort. For consumers, it could also mean higher prices down the road.

In West Texas, which has been affected by drought since last August, farmers have said they fear crop losses because of the lack of moisture in the ground. The drought has also increased the risk of wildfires and the need for firefighting resources.

In most of the state, the drought has not yet affected the water supply, but South Texas and areas served by reservoirs along the Rio Grande have already seen water shortage concerns, Neilsen-Gammon said, pointing to the Falcon Reservoir, which reached “historically low levels” this summer.

Many public water systems across the state have issued varying levels of water restrictions or asked the public to conserve water, according to a Texas Commission on Environmental Quality list from earlier this month.

A few public water systems in the counties of Uvalde, Denton and Kerr have also declared emergencies, a sign they could run out of water within 45 days, according to the TCEQ.

City officials in the North Texas town of Gunter warned in July that they could run out of water after residents failed to heed calls for conservation and two water wells malfunctioned.

In Uvalde County, five of the eight groundwater wells in the small town of Concan have run out of water, requiring leaders to truck water across town every day, the San Antonio Express-News reported.

What do the forecasts say about how long the drought will last?

Parts of Texas, such as the Rio Grande Valley, have seen rain recently, and more regions of the state could see rainfall over the next two weeks thanks to seasonal atmospheric changes and cold fronts moving southward, said Brad Pugh, a meteorologist for the federal Climate Prediction Center.

This does not mean the drought is over.

The center forecasts that La Niña will continue into the fall and likely in the winter, Pugh said. Chances for La Niña are expected to gradually drop from 86% to 60% during December to February, according to the center. Some forecasts suggest conditions in the Pacific Ocean could return to a “neutral” phase, during which sea surface temperatures return to near average, closer to the spring.

That means dry conditions in Texas could continue, especially later in the fall and winter, potentially leading to a multiyear drought, Nielsen-Gammon said.

“We’re in a fairly wet pattern right now for the rest of August, which will at least help stop the drought from getting worse,” he said. “But since the outlook favors dry conditions, we’re probably still going to be in drought for several months in most places.”

Droughts can “persist for multiple years or even decades,” Nielsen-Gammon said, but most last only a few months to a few years because El Niño and La Niña shift irregularly every two to seven years.

If the drought continues, what happens next?

Parts of the state are seeing temperatures similar to those during Texas’ 2011 drought, the driest year on record in the state, but there has been more rainfall this year than in 2011, Nielsen-Gammon said.

Still, a prolonged drought could affect crops in the winter and spring and limit feed for livestock.

“Soil moisture in West Central Texas is generally not adequate to allow winter wheat to be planted and germinate and get established, so rain in the next month or two would be critical for getting that crop off to a good start,” Nielsen-Gammon said.

The 2011 drought cost an estimated $7.62 billion from crop and livestock losses. The economic impacts of the current drought are not yet clear, but Nielsen-Gammon said he expects it to be in the billions.

“And the longer the drought goes on, the more the impact starts shifting from agricultural issues to water supply issues,” he said. Depleted reservoirs would require even more rainfall to recover, he added.

What are ways to conserve water?

Check to see if your city or public water system has issued water restrictions or requested water conservation on the TCEQ’s list.

One of the first steps recommended to conserve water is to cut back on water use for landscaping, Nielsen-Gammon said.

If you’re going to water your lawn, it’s best to avoid doing it in the middle of the day to try to prevent water from evaporating. It is also recommended for the water to be released closer to the ground, particularly if you use sprinklers.

Checking for leaks in your home and turning off the faucet when you’re not actively using water, like when you brush your teeth, shave or shower, can also add up and save gallons of water.

You can also take bigger and longer-term steps by changing your lawn to include plants and grasses that require less water, setting up a rainwater collection system and establishing ways to redirect and reuse “gray water” like bath water.

Disclosure: Texas A&M University has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

Photo: Cotton fields near the High Plains town of Ralls, about 30 miles east of Lubbock, on Wednesday, June 22, 2022. Like much of Texas, the High Plains and Panhandle are facing drought conditions and extraordinary heat. Credit: Trace Thomas for The Texas Tribune

BY MARÍA MÉNDEZ with Texas Tribune.